Module 3: Cash Flow

Exercise #2: Bob & The Wired Cup

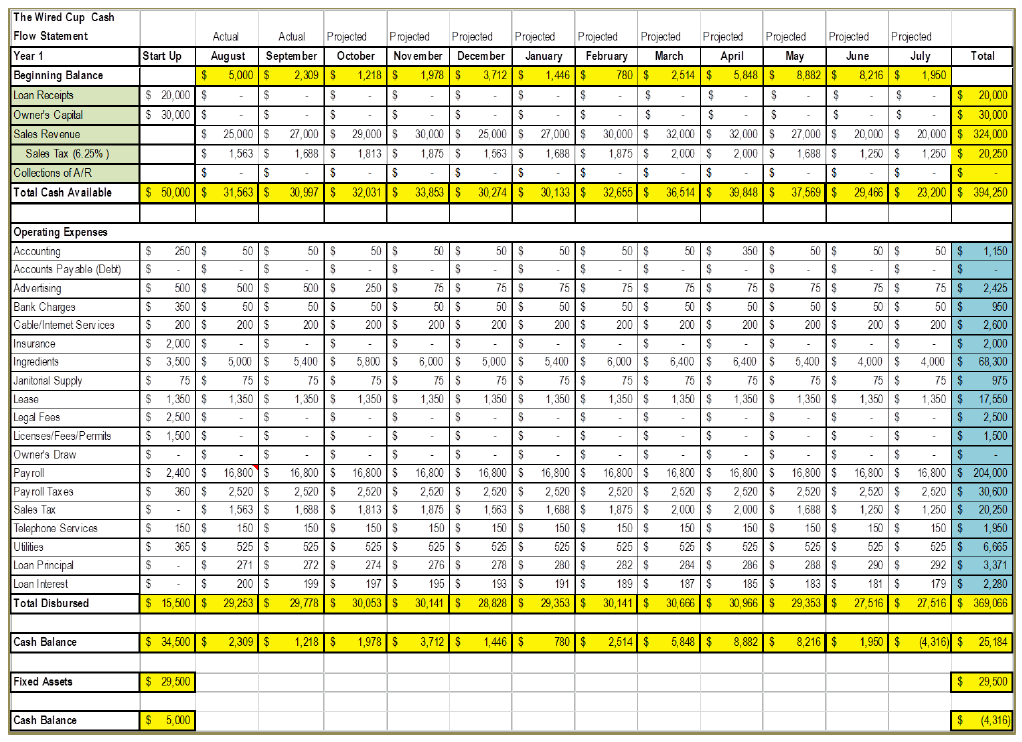

Let’s return to our old friend Bob and his business The Wired Cup. Now that he has a month or two under his belt, he can update his original cash flow projections using real world data. Take a look at his projections for the year and see if you can see any issues with his projections.

We’ll take a closer look at the projections below the chart.

Bob is basing projections on actual data – August and September in this example. He doesn’t know how much the seasonality of college life will affect his business. He assumes it will be significant, especially the next summer when students return home.

The first column lists all the money Bob has invested so far. This includes his loan, the money he has put into the business from his savings, and the money that has gone out for operating expenses (accounting, debt, advertising, utilities, etc.). Ordinarily, startup costs wouldn’t be represented on a balance sheet, but since this is a new business, it helps Bob understand his cash position from the moment he opened his business.

The next two columns are for August and September. These are the actual expenses of running the business. Bob had the $5,000 leftover from his initial investment and the bank loan. His gross sales for August were $25,000 plus sales tax of $1,563.

The sales tax must be entered as a separate line item in your spreadsheet and put in a separate bank account. You don’t want to comingle the money you take in with the money you owe the government. This is not your money to use. You will need to pay it to your local, state and federal tax accounts, usually quarterly or monthly. You want to do the same if you have employees and need to pay payroll taxes. It can’t be used to fund your business operations, so it can’t be comingled.

In August, The Wired Cup had a total inflow of $26,563 (revenue + sales tax). That means Bob’s total available cash was $31,563, adding in the $5,000 in cash he had left after covering all his startup costs.

As with most businesses, Bob has monthly fixed costs (lease payment of $1,350; cable/internet $200) and variable costs that vary from month to month, such as advertising and utilities.

Every business has decisions to make that reflect these fixed and variable costs. For example, you can decide how much space to lease for your business, how much debt to carry, where and when to advertise, and how many staff you’ll employ.

Between the money coming in from sales and the outgoing funds to cover the fixed and variable costs, Bob ended up with $2,309 at the end of the August. As he starts September, he enters this amount in the category at the top that says Beginning Balance.

As he did for August, he enters all his sales, taxes, and actual fixed and variable costs. He started with the $2,309 left over from August. Sales were $27,000 and taxes were $1,688. This means the café’s gross revenue for September was $30,997. His expenses were $29,778, in part because the cost of ingredients went up. This leaves Bob with $1,218 as the starting balance for October.

The good news is, Bob managed to cover his costs in the first two months.

Projecting annual cash flow

Two months of business doesn’t give Bob the best data to work from. There are a lot of variables that can affect a business and its bottom line. In working out his various scenarios, Bob has three options:

- Best case: This would be an ideal situation where all your dreams come true.

- Worst case: This would be a much more conservative scenario where you do not get the sales revenue you would hope for and costs are higher.

- Most likely: This would be like the Goldilocks story—not too hot, not too cold, but just right. It is the most likely scenario, somewhere between a best and worst case.

Bob chooses to go with the last scenario. He knows that students and faculty leave for summer vacation, so he plots a slow drop in sales and then a negative flow of $4,316 starting in June and carrying over into July.

This is not something you want to do in a business. Negative cash means you are out of business.

What you want to achieve is a continuous flow of excess cash. If you’ve noticed that Bob still hasn’t paid himself, congratulations. So far he’s making ends meet but isn’t socking away any excess profits so that he can get paid. Everything is going back into the business, as evidenced by the ending balance of one month being the starting balance of the next. Nothing is retained for the owner’s draw, which is the owner’s paycheck.

Let’s see what Bob can and can’t do in the next section…