Crunching the Numbers

Step 2: Assess the Probability

Now, let’s look at the second part of the equation, the probability this scenario will occur.

Let’s return to our convenience store. If you do some statistical research, you’ll find that there is a 6% chance that any convenience store will be robbed at any particular point. That is the nationwide average.

But let’s say that you know that your store has been robbed twice in the last five years and it’s in a tough neighborhood that has a high crime rate overall. While the statistical chance is only 6% nationally, experience tells you it will be higher for your locale. You choose to give it a 20% chance. This means that while a robbery would have a medium impact on your business, there is only a one in five chance that it will happen at any particular point in time.

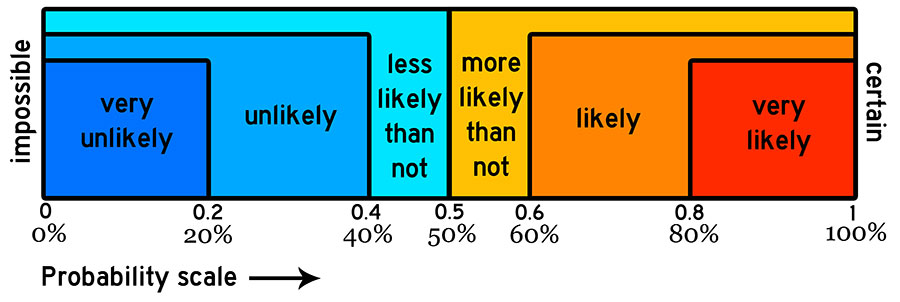

For each potential crisis you’ve listed, what is the likelihood of the event occurring? Is it an almost certainty, a once in a blue moon chance, or somewhere in the middle? Assign a numerical value to the probability as a percentage on a scale from 0% (no chance at all) to 100% (absolute certainty). It’s O.K. to guess at this point, but if you do, err on the side of greater probability, not less. You can always adjust the numbers later, but it’s easy to minimize the chance something will happen because we like the comfort of best-case scenarios.

The final ranking for this scenario then would be expressed like this: 6.0/20 – a 6.0 average for the impact it would have on your business and a 20% chance of it occurring.

Though the chance of it happening is low, you can still do something to reduce the impact of a robbery if you wish. For instance, you could install another security camera or two, keep less cash on hand, add more lighting in the parking lot – the list goes on.

But before you call a security company or electrician, think more about the crisis itself. Is the potential impact worth the cost? How much will it cost you to add these extra security features? Is it substantially more than it would cost to do nothing? Conversely, how would the numbers change if you arm your employees and encourage them to be proactive rather than reactive? Is that worth the money you’d lose?

As you run the numbers, remember that there are usually two levels of cost. There are hard costs and soft costs. Hard costs are the actual dollars a crisis costs you, which can include preventative measures, damage to the property or losses in income caused by the situation. In contrast, soft costs are the things you can’t always readily see: decreased productivity, increased absenteeism, workers’ compensation claims, increased turnover, erosion of community support, bad publicity, etc.

Depending on the crisis at hand, the cost of intervention may appear to equal the hard costs of a possible loss. But the soft dollar losses can create a draining effect on your business as you continue to lose revenue long after the initial crisis has passed, often without noticing it until it’s too late.

Typically, the more attention your crisis receives in the news, the more likely you will experience a cost in soft dollars. This soft dollar loss can occur over weeks, months or even years. You want to go through this process and analyze hard and soft dollar costs for each crisis you have identified.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Why You Need to Plan Now!

3. The Four Stages of a Crisis

4. Assessing Impacts

5. Assessing Probabilities

6. Putting It All Together

7. Plotting the Results

8. Rinse & Repeat

9. Developing an Effective Plan

10. Plan Components

11. Crisis Response Modules

12. Decision Trees

13. Resuming Operations

14. Summary

15. Templates & Resources